Imagine an abundance of gold, where everyone from the noble upper class to the warriors to the common people to the slaves all were covered in gold ornaments. Being passed down from generation to generation or being buried with your gold possessions to take with you to the afterlife. This was the life of our ancestors prior to the arrival of the Spaniards in the 16th century. All genders, all social classes wore gold from gold necklaces, earrings, bracelets, armlets, to even extending that love for gold to making a threaded belt and hilts of swords and daggers made of gold.

“I do remember that once when I was solemnizing a marriage of a Bisayan principala, she was so weighed down with jewelry that it caused her to stoop — to me it was close to an arroba or so (1 arroba = 25 lbs.), which was a lot of weight for a girl of twelve. Then again, I also heard it said that her grandfather had a jar full of gold which alone weighed five or six arrobas. Even this much is little in comparison to what they actually had in ancient times.” – Francisco Ignacio Alcina, 1668

When the first Spaniards arrived on the islands of what is now known as the Philippines, from Magellan to Legazpi, they all recorded the gold jewelry that was numerous among the people they saw. They were shocked on the amount of gold they saw on a people who for the Spaniards dressed almost to naked, with the men who wore g-strings known as bahag and other various local terms, and their form of clothing was through their tattoos and gold ornaments. To the Spaniards they saw gold as a symbol of wealth, however the people they saw wore it as a part of their everyday clothing attire regardless of class and gender. One of the records that most illustrate this abundance and distribution of gold are the illustrations of pre-colonial Pilipinos in the Boxer Codex manuscript which is the only known manuscript from the Philippines to use gold leaf. Gold was actually the most mentioned topic in old Spanish historical accounts as it was everywhere. Numerous accounts mention how it could be seen on the persons of both men and women, child to elderly, noble to slave, and that these people could tell exactly where the gold came from by just looking at it.

“Nothing in the Indonesian repertoire or in the empires of Angkor [Cambodia] or Bagan [Myanmar], compare with these. It is unlikely that any ornament of the ancient world is comparable to the sheer scale of the goldsmiths’ ambitions or in the sense of excitement that the artisans themselves surely must have felt on beholding their own creations.”– John Micsik, Southeast Asian Studies Program, National University of Singapore

“The Moros [of the Philippines] understand the laws of gold better than we do.” -Francesco de Sande, 1577

“They would rather keep it below the ground than in cash boxes because since they have wars, they can steal it in the house but not in the ground.” – Juan Martinez, 1567

“They mix it [gold] with copper so skillfully they will deceive the best artisans of Spain.” – Hernando Riquel, 1573

“The many different kinds of large and small beads, all of what they call filigree work here…is clear evidence that they did careful, delicate, and beautiful work even better in their antiquity than now, since all ancient goldwork is of higher gold content and craftsmanship, than what is being made now…[ like the kamagi], a piece of jewelry of greater value and curiosity than could be expected of a people apparently so crude and uncivilized.” (Alcina, 1668)

There were various systems of valuing gold that existed in the islands.

Guinogulan — 22 carats, not traded

Panica — 16-18 carats, 5 pesos per tael

Linguingui — 4 pesos per tael

Bielu — 3 pesos per tael

Malubai — 2 pesos per tael

— Gov. Francisco de Sande (1577)

Ariseis — 23 carats three granos, 9 eight-real pesos per tael

Guinogulan — 20 carats, 7 pesos per tael

Orejeras (Panica) — 18 or 19 carats, 5.5 pesos per tael

Linguin — 14 – 14.5 carats, 4 – 4.5 pesos per tael

Bislin — 9 – 9.5 carats, 3 pesos per tael

Malubay — 6 – 6.5 carats, 1.5 – 2 pesos per tael

— Martin Castanos, Procurator-General (1609-1616)

Guinuguran — not traded

Ylapo — not traded

Panica — not traded

Linguinguin — four pesos a tael

Malubay — two pesos a tael

Bizlin — two pesos a tael

— Andres de Mirandaola (1569-1576)

Idelfonso de Santos found the following terminology used in the Tagalog language for reckoning gold purity:

Ginugilan — 22 carats

Hilapo — 20 carats

Palambo — 20 carats

Wasay — 20 carats

Urimbuo — 18 carats

Panika — 16 carats

Panikang bata — 14 carats

Lingginging — 12 carats

Lingginging bata — 10 carats

Bislig — 8 carats

And from William Henry Scott, also using Tagalog sources:

Dalisay — 24 carats

Ginugulan — 22 carats

Hilapo — 20 carats

Panangbo — “Somewhat less than 20 karats”

Panika — 18 carats

Linggingin — 14 carats

Bislig — 12 carats

The panika and below were the ones usually traded while the more pure gold was kept as bahandi, heirlooms, to be passed down from one generation to the next.

Gold was refined using the salt process where it was molten into molten gold and the goldsmith would add salt, rock salt, and or/saltpeter. This was done to form compounds with other metals such as silver and copper and separating them from gold. This process was repeated until the desire purity of the gold was reached.

tumbaga — gold mixed with copper

sumbat — gold mixed with silver

hutok — gold mixed with copper and silver

malamote — gold mixed with silver

sombat — gold mixed with various metals including copper, brass and silver

lauc — any gold alloy

“…what distinguishes the Philipipne goldworking tradition is that is displays a level of refinement matched only by the kingdom of Java. Although gold jewelry played an important role in mainland Southeast Asian kingdoms, such as those of Champa [Vietnam], Angkor [Cambodia], and Dvaravati [Thailand], these depended mostly on simple sheet and repousse methods of construction, rarely displaying the technical complexity and level of skill evident in the Philippine workmanship. only the Javanese goldsmiths rivaled their Philippine counterparts…”

– John Guy, Curator of South and Southeast Asian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Gold Religious Carvings

Prior to the arrival of Christianity, majority of our ancestors were Animists and Polytheists, believing in numerous gods and goddesses and the spirits the live alongside us. Prior to that we have evidence based on artifacts and the oldest written document, the Laguna Copperplate, proving that at least in some parts of the Philippines at some point in our historical timeline our ancestors practiced a form of Hindu-Buddhist beliefs that is today seen in other parts of Southeast Asia. Some of these artifacts derive from gold artifacts depicting religious carvings of a well known Hindu-Buddhist goddess and some mythical creatures.

The Golden Tara of Agusan currently showcased in the Field Museum in Chicago. Photo by Anne Petersen

The Golden Tara of Agusan, was discovered in July of 1917 after a flood and storm swept through through Agusan Del Sur in the barangay Cubo Esperanza. After the storm a Manobo woman named Bilay Ocampo was on the banks of the muddy Wawa River where she eventually found the figure where it washed up from the river. The 21-karat gold figure dating to around 850 to 950 C.E. weighs 4 lbs and depicts a woman sitting in the lotus position in Buddhism, is ornamented with jewelry on her body, and wears a headdress. This figure turned out to be a representation of the Bodhisattva Tara.

In the words of UP scholar Dr. Juan Francisco, he described the golden statue as, ”One of the most spectacular discoveries in the Philippine archaeological history.” For more info on the Golden Tara I have already made a post talking about this goddess who is still worshiped today and the history behind the Golden Tara here.

Another gold artifact of religious significance is the Kinnari, half-bird, half-woman creatures who are renowned for their dance, song and poetry, and are a traditional symbol of feminine beauty, grace and accomplishment. The Kinnari was found in 1981 in Surigao along with other treasures.

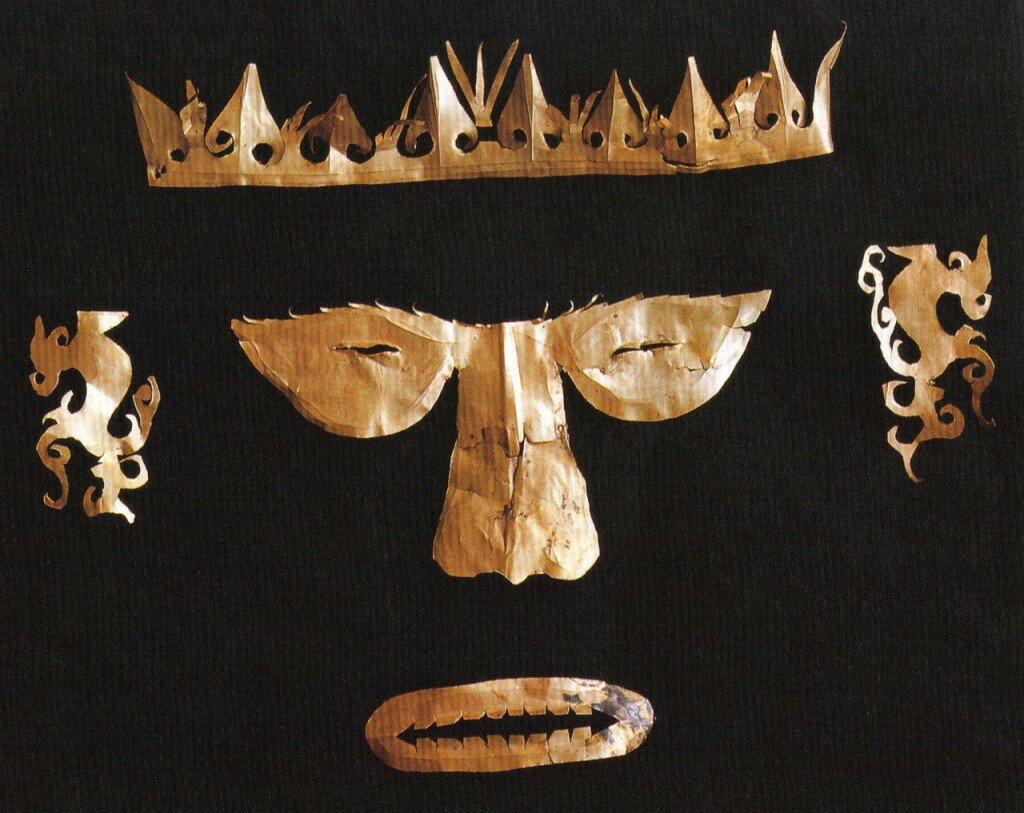

The Death Masks

“These natives bury their dead in certain wooden coffins, in their own houses. They bury with the dead gold, cloth, and other valuable objects—saying that if they depart rich they will be well received in the other world, but coldly if they go poor.” – Miguel de Loarca, 1582

Scribed swirls and waves on headbands and facial covers from Butuan inspired by waves or the niaga, the snake or dragon motif, which symbolized the sea, which the ancient Filipinos mastered. The abstract pattern expresses the dynamism of ancient Philippine civilization. Those patterns and motifs survive in the southern Philippine okir design tradition. Artisans used a stylus — perhaps just a pointed bamboo stick — to scribe the patterns on the hammered sheet.

Pre-colonial Gold Earrings

“All the women, and in some places the men, adorn the ears with large rings or circlets of gold, for that purpose piercing them at an early age. Among the women the more the ears were stretched and opened, so much greater was the beauty. Some had two holes in each ear for two kinds of earrings, some being larger than others.” – Francisco Colin, S.J., 1663

Earring depicting the mythical garuda, a bird like creature which is found in Hindu and Buddhist mythology.

Both men and women wore earrings and earplugs. They had their ears pierced, men with one or two holes per lobe, while women with three to four. Panika was the general term for rings and plugs worn in the lower hole (panikaan). They were also the term used for the finger-thick gold rings which were split on top to be fastened to the earlobe “like a letter O, in which Francisco Alcina mentioned “without being able to see the opening once they were inserted.” It was made by hammering a thin sheet of gold over a wax-resin mould, and it must be at least 18 karats to be soft enough to work. Some of these rings were hollow and others a solid gold heavy enough to pull the earlobe down until the ring actually touched the shoulder. In the Initao Burial Cave in Lekak, Cotabato, among the ceramic heads found was one that had holes through elongated earlobes for the rings.

The large gold plugs worn were known as pamarang or barat. Dalin-dalin were simple loops and palbad were the rosettes worn by women in the uppermost hole, dinalopang if it was shaped like a yellow dalopang blossom. Kayong-kayong was any pendant dangling from an earring and sang was a single ring worn in one ear only.

In Samar and Leyte were ear ornaments called uod, or caterpillar shaped ornaments, that were slit in the back so that they wrapped around the extended earlobe. This ear ornament can be seen on female figures carved on stone reliefs in Indian temples of the same period. The form is not seen in other parts of Southeast Asia, suggesting that there was a direct and intimate connection between Indian and Samarnon artisans.

The holes were made with a copper needle. The first piercings were made soon after birth while the next ones were made before the childs second year. A thick cotton thread was looped through the hole to keep it from closing. After the wound was healed the thread was then replaced with a series of gradually thicker bamboo or hardwood splints until the hole was large enough to fit the circumference of the little finger. It was then over time extended to the desired size by inserting leaves tightly rolled up to exert steady, gentle, pressure outwards.

If by any chance the distended lobes tore, the ends would be trimmed and the raw edges would be sutured together to heal the hole again. This procedure was know as kulot or sisip and it was more frequently asked by women as when women fought against one another they would go for each others ears first.

They even had terms for those without pierced ears, bingbing, and those whose ear lobes were naturally to short for a successful piercing and distending known as bitbit.

Illustrations depicting the gold earrings worn by our ancestors displayed in the Ayala Museum.

Photo by Cecilia Manguerra Brainard

Necklaces & Bracelets

Just like their earrings our ancestors were very fond of wearing gold necklaces, bracelets, armlets, rings, anklets, and gold chains. The most visual impact of this gold jewelry can be found in the illustrations in the Boxer Codex depicting our ancestors and which has been supported by the actual gold artifacts themselves.

Necklaces were created in the form of strands, chokers, and collars, which ranged from precious stones to gold beads. These gold beads included the four-sided matambukaw, the long hollow tinaklum, and the fancy pinoro finials with granules added to their surfice like tiny gold islands. Other beads were shaped like little fruits, arlay like Job’s-tears, tinigbi like the tigbi fruit, or bongan buyo like betel nuts.

In the Boxer Codex a passage on the Tagalogs mentions how men “wear many golden chains around the neck, especially if they are chiefs, because these are what they value most, and there are some who wear more than 10 or 12 of these chains…“. “The women carry much gold jewelry because they are richer than the Bisayans. Men and women also wear many bracelets and chains of gold on the arms. They are not used to wearing them on the legs. Women likewise carry around the neck golden chains that men do…”.

In Antonio de Morga’s account in his Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas, 1609, he mentions “chains of gold wound round the neck, worked like spun wax and with links in our fashion, some larger than others, bracelets on the arms which they call calombigas, made of gold very thick and of different patterns, and some with strings of stones, carnelians and agates and others of blue and white stones which are much esteemed among them.”

Necklace with beads shaped like auger shells (suso), Northeastern Mindanao, circa 10th–13th century, Ayala Museum collection.

Large necklace of granulated interlocking beads, Surigao Treasure, Surigao del Sur, circa 10th–13th century, Ayala Museum collection.

Gold bands were worn around the biceps and above the calves. These were called kasikas. Women tended to wear many bracelets on their arms for beauty as a way to attract attention through the jangling sound of the bracelets as they moved. There is even a term for when they would point to the sun and if the bracelets slid down the arm it was makadululu, a specific hour of the day as a form of time keeping.

Belts & Sashes

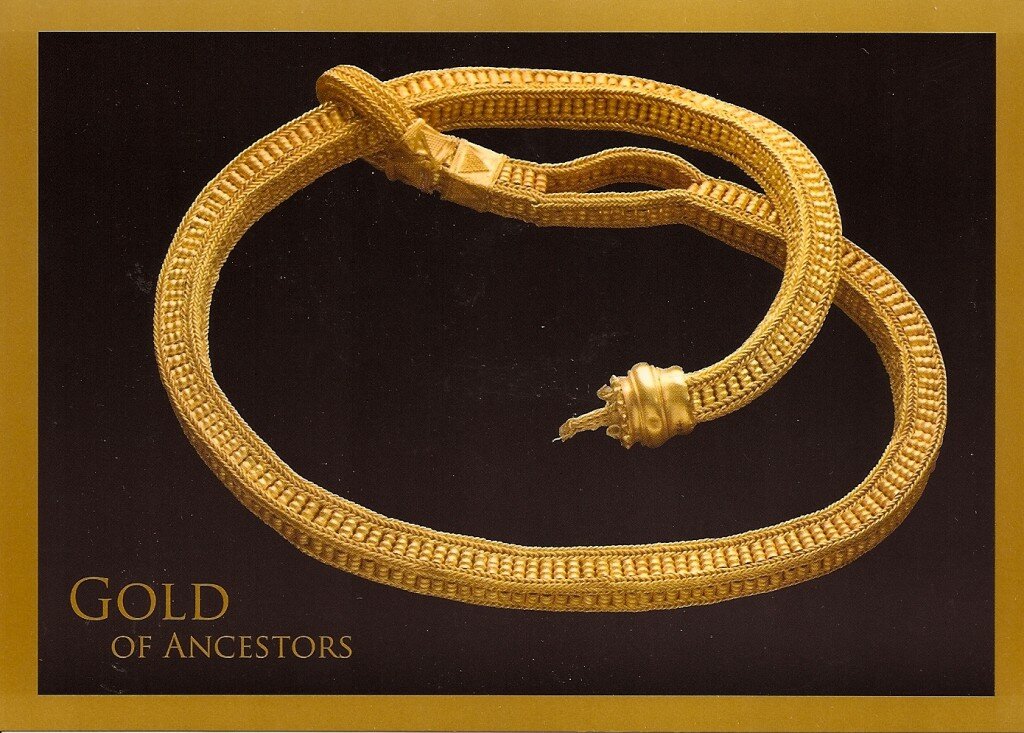

Along with their gold jewelry our ancestors also wore gold belts and sashes as part of their clothing. Some sashes were only used for ceremonial purposes and one such example is the Surigao Sacred Thread which weighs more than four kilos. These were worn by the data’s and rajahs as a symbol of their wealth and power. As a matter of fact we have a visual of something similar to the sacred thread found in one of the illustrations in the Boxer Codex.

The famous “sacred thread” unearthed in 1981 in Surigao del Sur is made of pure solid gold, weighs more than four kilograms, and is estimated to be about 1, 000 years old. (Ayala Museum.)

These sashes are reminiscent of the ones worn in Hindu paintings of deities and are the only ones recovered in the world. It’s something to marvel at because these sashes aren’t found in any place in the world and so far are the only ones physically made and only found in the Philippines.

Gold Teeth

Before the Spaniards arrived our ancestors decorated their teeth, from staining them black or red, to adding gold decorations. Antonio Pigafetta mentioned the decorative dentistry among the Visayans. In one of his passages he describes Rajah Siaui (Siawi/Si Awi)/Siagu of Butuan having gold ornamental teeth.

“He had three spots of gold on every tooth and his teeth appeared as if bound with gold.” Then in the Sanchez 1617 Visayan dictionary, there is a passage that says, “Pilay sohol ko nga papamusad ako dimo“ [How much will you charge me for gold teeh]?

Pusad was the general term for teeth goldwork, whether they were inlays, crowns, or plating. The mananusad was the dental worker, a professional who got paid for his services.

Halop, covering, included both plating held on by little gold rivets run through the tooth, and actual caps extending beyond the gum line, also secured by pegs. Bansil were gold pegs inserted in holes drilled with an awl called ulok, usually in a thumbnail-shaped field that had been filed into the surface of the incisors beforehand. If they were simple pegs without heads they looked like gold dots on ivory dice when filed flush with the surface of the tooth (like Rajah Siawi). But if the pegs were tack-shaped, their flat heads overlapped like golden fish scales (like the teeth on the Bolinao skull); or if round-headed, they could be worked into intricate filigreelike designs similar to beadwork. Of course, this goldwork was considered all the more effective if displayed on teeth polished bright red or jet black.

The most well known evidence of this gold decorative dentistry is the Bolinao skull found in the archaeological excavation of Balingasay Site, Bolinao, Pangasinan. Gold scales were observed on the buccal surfaces of the upper and lower incisors and canines. The dental ornamentation consists of pegging with gold plates in fish scale design or pattern with gold wire rivets.

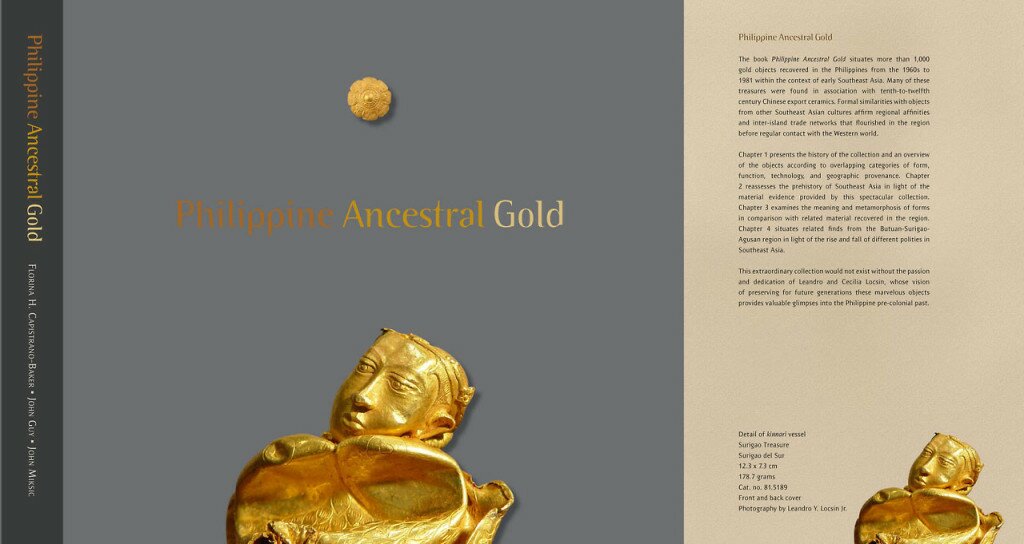

Philippine Ancestral Gold Book by Florina H. Capistrano-Baker.

If you want to browse through the more than 1,000 gold artifacts recovered from the Philippines I highly suggest looking at the book ‘Philippine Ancestral Gold’. Chapter 1 the history of these artifacts and an overview of their function, how it was made, and where it was found. Chapter 2 talks about the prehistory of Southeast Asia while Chapter 3 examines the meaning and metamorphosis of forms in comparison with related material recovered in the region. Chapter 4 situates related finds from the Butuan-Surigao-Agusan region in light of the rise and fall of different polities in Southeast Asia.

Philippine Ancestral Gold is edited and authored by Dr. Florina Capistrano-Baker, former Ayala Museum director, co-written by John Miksic and John Guy, curator of South and Southeast Asian Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. The book also features stunning images by renowned photographer Neal Oshima and designed by Ige Ramos, making the reading of Philippine Ancestral Gold both academically enriching and visually entertaining.

Where to buy the book:

The Ayala Museum Shop

Arkipelago, The Filipino Bookstore

NUS Press Singapore (ships mainly to countries in Southeast Asia except the Philippines)

These artifacts breathe life into our history, particularly our precolonial history prior to the arrival of the Spaniards. Can you imagine the 10th to 16th centuries when our ancestors processed these gold and used them in their clothing attire and everyday use? They even made bowls made out of gold. What is interesting is how all the social classes and genders wore some amount of gold even to the slaves. It wasn’t just something to signify wealth and power but it was a cultural norm to wear gold as it was believed along with tattoos it would grant safe passage to the afterlife.

Close your eyes and picture it. Brown sun kissed skin and black hair contrasting with the glitter of gold ornaments decorated on their body. If you are awestruck on the beauty imagine the Spaniards when they first laid their eyes on our islands?

Forget and cast aside the notion that our ancestors were nothing until the Spaniards arrived and weren’t civilized. We were known for our gold throughout Southeast Asia to even being the major exporters of gold to places such as Java and Borneo. We have designs such as the uod earring that is uniquely found only in areas in the Philippines such as Samar-Leyte and Butuan with only one other place which is in India but only on carvings of stone reliefs in old temples in central India of women wearing the same exact earring that has only been found and recovered in the Philippines. We made clothing out of gold. Dagger and sword hilts were made out of gold. People from a wide range of social classes from the rich, noble classes to even the slaves wore gold. Now you tell me our ancestors weren’t “civilized” and were brainless savages with no history before the Spaniards came on our islands and colonized us. Because we had a history, a rich one, that we should be proud of and reclaim as part of our heritage. That this is who we are and our ancestors left their legacy with us.

[…] you’d like to learn more about the Phillipines (Wiki) -Click here. Thanks to this site I was able to come across more fascinating information, all Filipino related and heres where […]